In the wake of

Charlottesville, the question of how best to respond to a growing and

emboldened fascist movement is pressing. People, by and large, take one of two

lines.

The Antifa line is: punch Nazis. That is, confront fascists whenever and

wherever possible, show them that their public presence will not be tolerated,

and try to make them scurry back to their holes to hide in the dark.

The

liberal line is: sunlight kills more Nazis than punches. That is, speak out and

hold demonstrations, if necessary, but don’t respond with violence, which will

only spread and encourage the fascists to become more radical and dangerous.

By

and large, people taking one line don’t have any patience for those taking the

other. Liberals think Antifa play into fascists’ hands, and escalate social

upheaval. Antifa think liberals give cover for fascists, and roll over in the

face of the growing threat.

I’m not going to take

sides on this question of tactics. Not because I don’t have an opinion (my

opinion: the Antifa are usually right about the present situation in the US),

but because I want instead to call attention to certain features of both

arguments, features that (a) are endemic to arguments about political tactics,

and that (b) make it very hard to even imagine settling those arguments in the

same time-scale in which they are made and are salient as motivational and

justificatory frameworks for action.

First of all, both

sides in this non-debate rely on a privileged stock of historical examples. The

Antifa think, especially, of the Battle of Cable Street, when rioting Londoners

stopped Mosley’s British Union of Fascists; the BUF never recovered. The

liberals think, especially, of Weimar Germany, where they see escalating street

battles between fascists and communists preparing the ground for Hitler’s rise.

These different

historical lodestones derive from different analyses of the social dynamics of

fascism. Liberals tend to see the fascist seizure of the state as a backlash

phenomenon: increasingly violent social struggle stokes the demand for “law and

order,” which the authoritarian far-Right is able to capitalize on. The thought

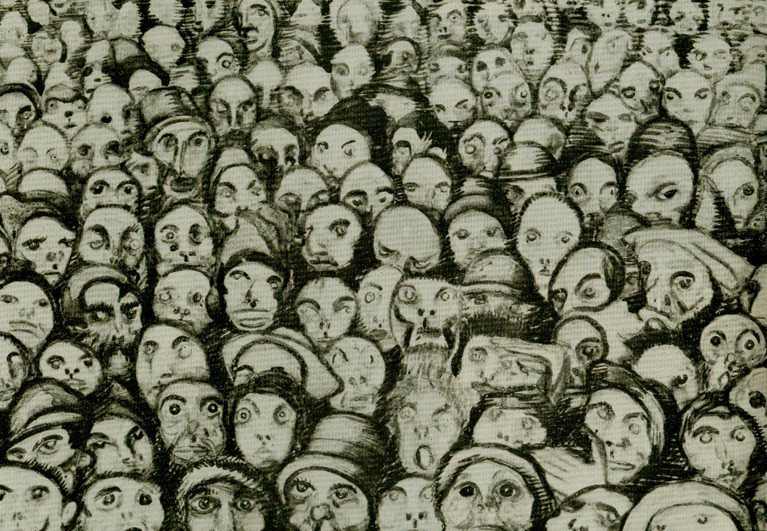

is that most people are basically apolitical, and just want to go about their

day-to-day lives. The more political disorder – of whatever sort – intrudes

upon that day-to-day, the more likely this mass of people is to become reactionary,

to demand that someone, anyone, put an end to the protests, the fighting, the

disruption. If this is right, then keeping the political temperature down, and

keeping the state’s monopoly of violence intact, seems like the safest path.

The Antifa, of course,

thinks this is not right. For the Antifa Left, the state is not a third

party mediating social conflicts; it is on the side of the dominant party in

those conflicts. If you expect the cops to handle the fascists, you’re going to

be disappointed to find out that too many of the cops are the fascists.

To be sure, there are

plenty of far-Left analyses that stress the danger of backlash. Gramsci, for instance, advised communist partisans not to mimic the fascists’

militia units lest the symmetry of the opposed civil warriors license the

state’s suppression of “all sides” – a suppression which would inevitably be

led by the military and police elements that also support or even comprise the

far-Right’s militia cadres. Precisely because the Left sees the state as on the

side of the dominant, it has always worried about provoking the “legitimate

monopolists” of violence. This is why the Left ought to always prefer (and

does, in fact, usually prefer) public, mass struggle to clandestine and

small-cell operations.

However, it is also

why the Antifa do sometimes embrace tactics that especially rile liberals.

Because Antifa expect the police to be on the side of the fascists, they are

especially wary of being identified. Hence, they are especially wary of being

filmed. Hence, they sometimes attack reporters covering protests. This seems to

have happened twice in Charlottesville, and it has Jake Tapper and Jonathan

Chait especially up in arms.

Fundamentally,

liberals don’t want private individuals making judgment calls about when

physical violence is appropriate. And they don’t want this because they think

such private judgments are both unaccountable and given to indefinite expansion.

I understand this liberal perspective. I don’t want unaccountable

people making decisions about the meting out of physical violence, either. But

I also think that liberals (a) overestimate how accountable the public authorities

are for the violence they mete out, and (b) underestimate the checks that Antifa

ideology and organization place on Antifa violence.

Leaving the policing of

violence to the authorities is not, in the world we actually live in, leaving

it in democratically accountable hands. And whatever tendency there might be

for political justifications of violence to expand their mandate, this tendency

runs up against certain counter-tendencies. It is easier to maintain the discipline,

fervor, and group-cohesion necessary for mounting effective street battles in the

face of actual, armed Nazis, but

much harder to do so with each step on Chait’s slippery slope of inference.

More importantly, for

me, is that the liberal opposition to Antifa tactics – like the justification

of Antifa tactics themselves – relies upon a predictive model of social and

political dynamics that operates on a timescale a thousand times larger than

that of the Twitter controversy cycle. To be frank, we cannot know whether the

Antifa opposition to the brown shirts of Charlottesville helps or hurts the

struggle against fascist resurgence in America.

At some point in the future,

perhaps we will be able to retrospectively ascertain this, but even this is

unlikely. Certainly liberals do not look at the Battle of Cable Street and say,

well, in that case Antifa tactics worked. Rather, they will explain the failure

of fascism in Britain by pointing to the stability and good order of the

British government, the elite consensus around the rule of law, or some such.

And the Antifa will certainly not grant that communist battles with Nazis in

Weimar Germany drove the electorate into the arms of the Right. Even if each

side granted the other its preferred historical case, there would be no basis

for generalizing the conclusion.

In the end, we all

want to act as if the deeds of a discrete set of addressable agents are

consequential and variable, even as we treat the actions and reactions of everyone else as predictable constants. Liberals

want to hold Antifa responsible for any reactionary backlash. Antifa want to

hold those who stand by and do nothing responsible for the belligerence of the

far Right. And we may not have the conceptual tools to do otherwise, to knit

together our ethical discourses of individual responsibility and our social

scientific discourses of large-scale movement and change.

The long-term and

large-scale dynamics of history are always the elephant in the room. If there

is no agreement about those, I don’t see how there could ever be any rational

argument about political tactics.