Daniel Oppenheimer has a very thoughtful essay on Mark Lilla and Corey Robin in the Washington Monthly. Among his observations is this: "Modern secular liberal society, of the sort Lilla prefers, will survive and flourish only if it’s able to reckon with the insights of those who critique and reject its premises. In fact it’s one of the necessary virtues of liberal society, for Lilla, that it’s capable of reckoning and sometimes even reconciling with its critics and haters. It’s also one of the responsibilities of liberal intellectuals to act as facilitators of this process." I think this really does get at the self-conception of many liberal intellectuals.

But then there is also this: "From this perspective an intellectual like Robin, who conspicuously rejects that conciliatory role, makes sense as a villain. And yet by this standard of villainy, many of the reactionary intellectuals whom Lilla respects and even admires would count as villains. These were people who had no interest in serving modernity, or contributing to its stability, because they saw it as hollow or rotten at its core, not worth serving or shoring up. They were not, in other words, liberal intellectuals, and had no desire to be. I would guess that Robin would say the same of himself, though from a very different ideological vantage point than most of Lilla’s subjects. So why not extend to him, and to the class of left-wing intellectuals of whom he’s fairly representative, the same intellectual courtesy, the same kind of sensitive, nuanced, historically informed and emotionally reserved critical treatment that Lilla is able to give to the subjects of his book, from whom he has more distance, either in time, space or ideology?"

Yes, why not? Why are many liberal intellectuals more understanding and sympathetic -- and astute -- readers of the anti-liberal Right than of the anti-liberal Left?

This has me thinking of an argument Philip Pettit makes in "On the People's Terms." Arguing against Isaiah Berlin's conception of freedom as non-interference, Pettit subjects it to what he thinks is a reductio ad absurdum. He argues that, if we are free so long as we are not being coerced or threatened, then this entails "that ingratiation -- toadying, kowtowing, and cosying up to the powerful -- can give you freedom of choice." It is not a very charitable or sympathetic thought, I admit, but I wonder if what Pettit thinks an absurdity is not actually a sincerely held belief of many liberal intellectuals: that getting cosy with the powerful can make you free.

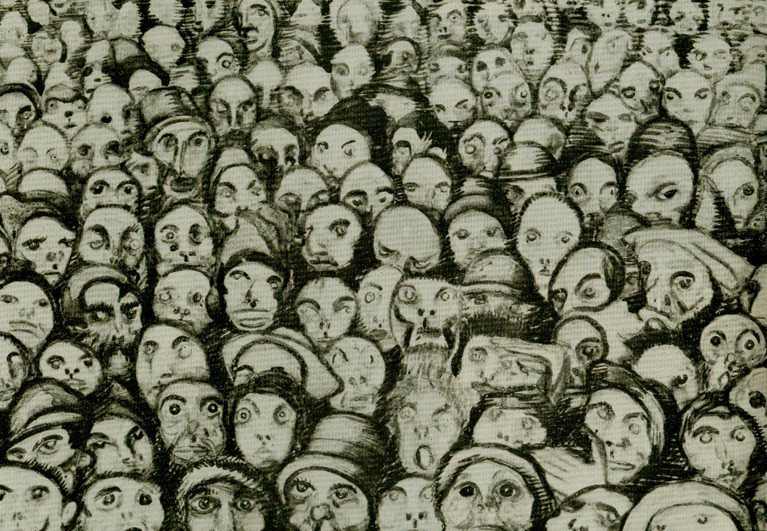

When Lilla attacks Robin, when Jonathan Chait attacks young leftists, the animating intuition is that if the outsiders, rebels, and radicals of the world would just be nice to those in positions of power, their complaints would, if not evaporate, at least be significantly ameliorated. They can put themselves easily in the shoes of those who rule and govern, and can appreciate that ruling is hard. They also think that large differentials of power and wealth are inescapable, and so we ought to mitigate their dangers by attending to the resentments and complaints of the wealthy and powerful, to keep them in good humour lest they desire to employ their wealth and power more intrusively and despotically. And, from where they stand, why would they think otherwise?